The Cost of Circularity: Why a True Closed Loop Must “Make Economic Sense”

As the circular economy increasingly becomes a key strategic focus for businesses, the concept of a “closed loop” is no longer just a symbol of environmental responsibility—it is also seen as an embodiment of innovation and social accountability. However, after investing significant resources into product recovery and material recycling, many companies face a fundamental question: If circularity itself does not “make economic sense,” can it truly be sustained?

In reality, numerous green initiatives find themselves caught between idealism and commercial practicality—recycling systems are established, product designs are modified, yet the cost of closing the loop remains higher than using virgin materials, ultimately becoming a financial burden. This reveals an often-overlooked business logic: A true closed loop must create quantifiable economic value, not just moral satisfaction.

I. Three Hidden Costs of the Circular Economy

To achieve a commercially sustainable closed loop, the following challenges must be faced:

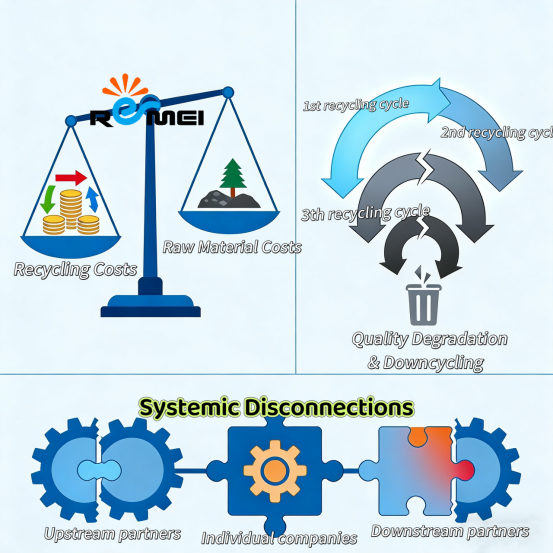

1. Recycling Costs Exceeding Raw Material Costs

When the total cost of collection, sorting, and reprocessing exceeds the direct procurement of virgin materials, the closed loop becomes a “green premium” for the company. This cost imbalance often stems from several factors: decentralized recycling networks drive up logistics and storage expenses; inefficient manual or primary sorting leads to high error rates; energy-intensive regeneration technologies yield low output rates. Without economies of scale and process optimization, companies often fall into the dilemma of “the more you recycle, the more expensive it becomes.” This additional cost, if absorbed by the company, directly erodes profits; if passed on to consumers, it may weaken price competitiveness and affect market acceptance.

2. Quality Degradation and Downcycling

Many materials experience performance lower quality and reduced purity during recycling, leading to “downcycling”—where recycled materials can only be used in lower-value applications. For example, plastics may undergo molecular chain断裂 with each thermo-mechanical recycling cycle, reducing mechanical properties; certain alloys accumulate impurities during remelting, making it difficult to restore original quality standards. This not only limits the number of cycles a material can undergo but also affects the reliability of end products and brand reputation. Without technological breakthroughs and process innovation, so-called “closed loops” may only delay materials’ journey to landfills, failing to achieve true high-value circularity.

3. Systemic Fragmentation

The efforts of individual companies are often constrained by the fragmented nature of the entire industry chain. Unstable upstream material supply, unclear downstream application scenarios, inconsistent cross-industry standards, and opaque data traceability systems… these systemic gaps prevent the smooth connection of circular flows. Even if a company designs a perfectly recyclable product, the lack of collection channels or market demand for recycled materials can prevent a true closed loop from forming. Without cross-enterprise collaboration and policy support, a circular system is like a machine missing critical parts, unable to operate sustainably.

II. Three Keys to Making Closed Loops Truly “Make Economic Sense”

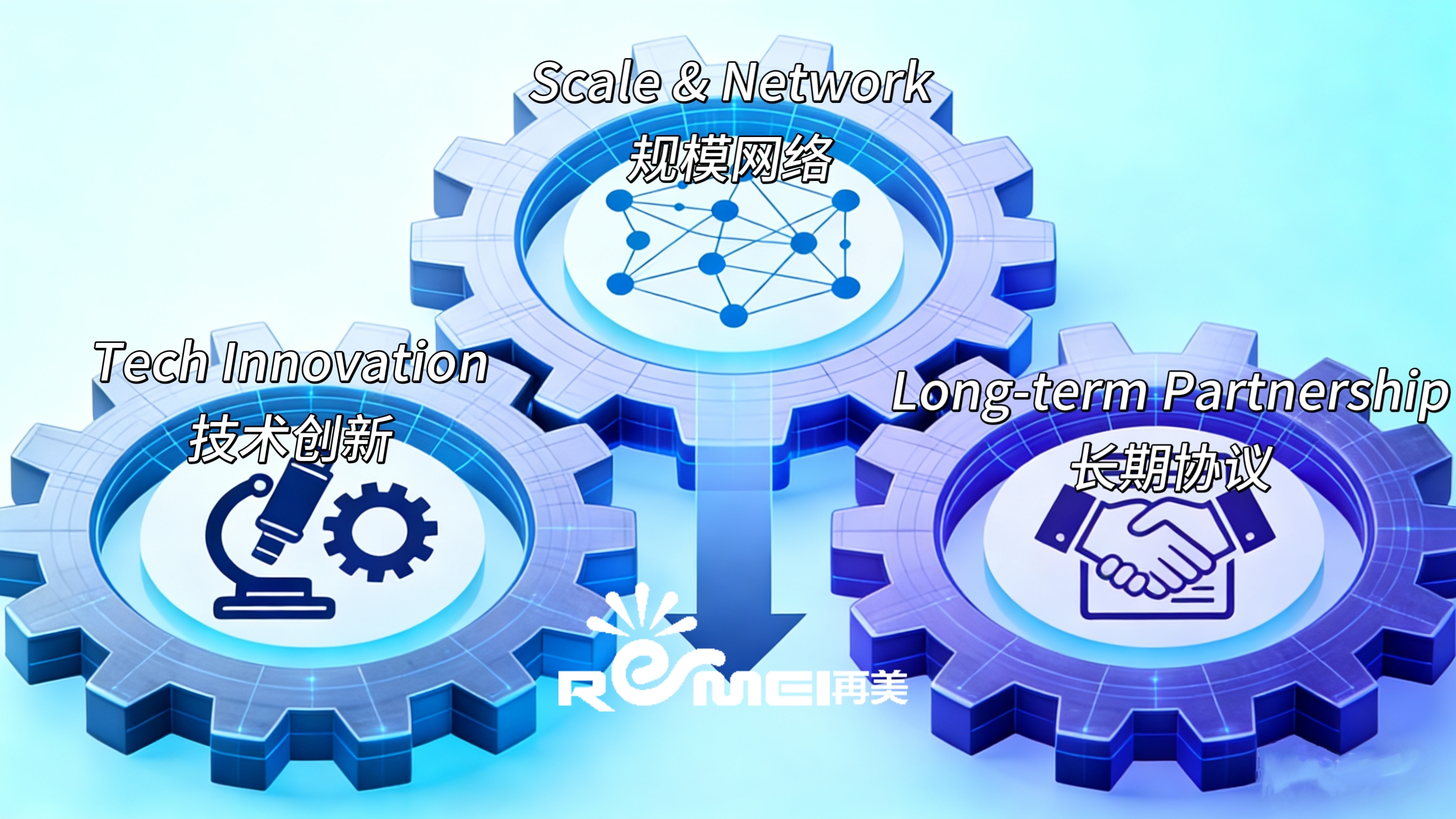

1️⃣ Technological Innovation as the Foundation

Approximately 80% of circular cost control lies in forward-looking planning during the design phase and technological breakthroughs in middle and back-end processes. Companies should systematically assess disassembly feasibility, material compatibility, and value retention rates from the early R&D stage, embracing the “design for circularity” philosophy. Simultaneously, by developing efficient sorting technologies (such as AI visual recognition, spectral analysis), green chemical recycling processes, and performance-enhancing additives, the quality and consistency of recycled materials can be improved—thereby lowering downstream remanufacturing costs and expanding high-value applications.

2️⃣ Building Scale Networks to Enable Efficient Material Flow

Closed loops are not isolated corporate actions but require stable, efficient collection and logistics networks. Integrating decentralized recycling resources, optimizing transportation routes, and matching supply with demand through digital platforms can significantly reduce per-unit operational costs. Examples include:

Establishing regional recycling hubs to process multi-category waste, improving equipment utilization;

Adopting “product-as-a-service” or subscription models to track product flow, increasing recovery and reuse rates;

Transforming circularity data into carbon footprint labels, green certifications, or carbon credit assets, opening new revenue streams.

3️⃣ Establishing Long-Term Partnerships to Stabilize the Circular Value Chain

The circular economy requires substantial upfront investment and has long payback periods, necessitating stable collaboration across the industry chain. By signing long-term recycled material purchase agreements with brands and manufacturers—locking in demand and pricing—companies can confidently invest in technology upgrades and capacity expansion. This trust-based partnership helps jointly plan technology roadmaps, share R&D costs, and build traceability systems, creating a virtuous ecosystem of “shared costs, shared benefits.”

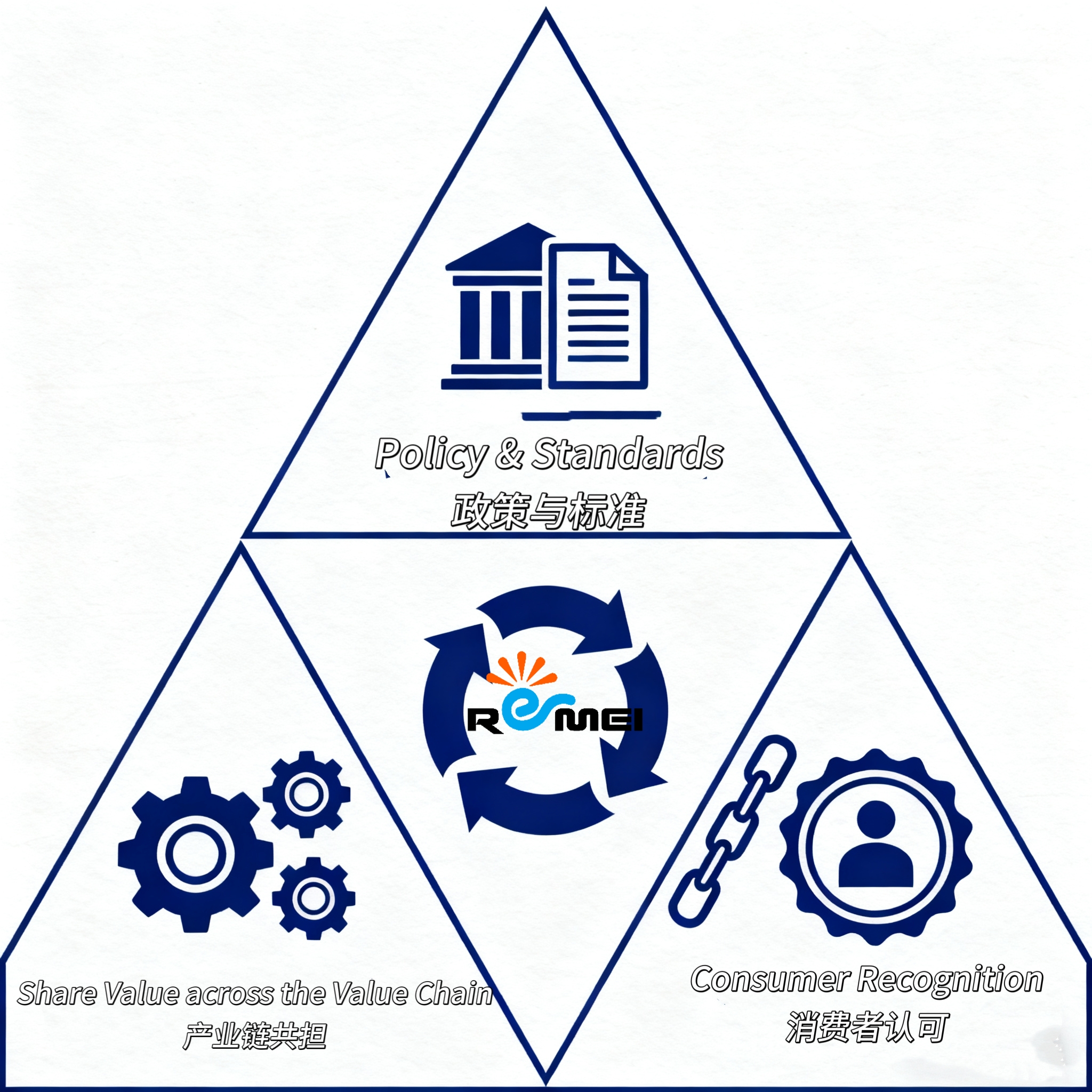

III. The Essence of Closed Loops: An Efficiency Revolution and Value Redesign

The ultimate goal of the circular economy is not to build an idealized theoretical loop but to create a practical system that is economically sustainable and environmentally beneficial. Only when circularity “makes economic sense” commercially can it transform from a cost burden into a source of competitive advantage.

This is not merely an environmental initiative but an efficiency revolution spanning the entire product lifecycle: reducing circular costs through refined operations, enhancing material value through technological innovation, and optimizing resource allocation through systemic collaboration. It is also a value redesign: shifting from the linear “take-make-waste” consumption model to a “design-circulate-regenerate” value retention model, uncovering new business opportunities within resource loops while reducing environmental impact.

We believe that a sustainable future begins with clear business logic.

If your company is exploring circular economy solutions or seeking to reassess the circular potential of your supply chain, we welcome further discussion to jointly build a closed loop that truly “makes economic sense.”

Leave a reply